This article has been reproduced from the July 1939 issue of the American Collector.

American Engraved Powder Horns

By Stephen V. Grancsay

Curator of Arms and Armor

Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

(All illustrations from the J.H. Grenville Gilbert Collection, Metropolitan Museum)

THE period of the French and Indian War was a map-making era. Since much of the country was not chartered, it is perfectly logical that a map should be engraved on a powder horn. For the horn was the indispensable accessory of the settler’s rifle, the greatest of all American map makers. The great pathfinder, Christopher Gist, in 1750, as the agent and surveyor of the Ohio Company, was sent to explore the region west of the Alleghenies. While on this journey, King Beaver and Captain Oppamylucah, chiefs of Delawares, propounded to him the following question, which Gist confesses he “was at a loss to answer. The French claim all the land on one side of the River Ohio and the English all on the other side. Where does the Indian’s land lie?”

The very powder horns that often played a part in answering that question may be seen in the J. H. Grenville Gilbert Collection of American powder horns now on exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum. Here are horns of heroes of the French and Indian War and of the American Revolution and most of them are engraved with the soldier’s name, a date, a rhyme, or a map. The horns shown are primarily those of good workmanship, those which were engraved by gunsmiths and silversmiths. However, some of the horns were carved by the soldier himself with a jackknife. And as scratched work is a primitive form of graphic expression and surface decoration, these powder horns are valuable as an expression of decorative folk art. Furthermore, they are also valuable for the human interest which their inscriptions suggest. Each of the horns tells its own story.

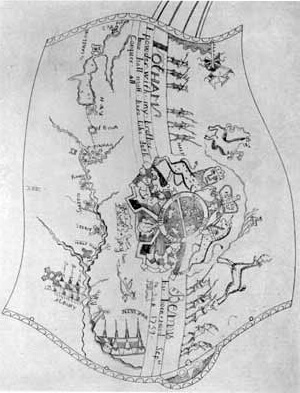

One of our New York map horns (Illustration IV) has considerable interest for it bears the name of the owner, his place of residence, and a date (“Iotham Bemus his horn maed Septr the 30, 1759 Stillwater”), together with drawings, resembling Indian pictographs, of soldiers armed with bayoneted guns, and a rhyme (“I powder with my brother ball most hero Like doth Conquer all”). The map terminates at CRV POI (Crown Point) with the inscription “TO CARELONG” (that is, Fort Carillon, as Fort Ticonderoga had been called). Jotham Bemus was born in 1738 and died in 1786. He kept the only tavern of any note between Albany and Fort Edward, and today there is a stone tablet marking its site. The family name is associated with the important battles fought in the vicinity of Saratoga.

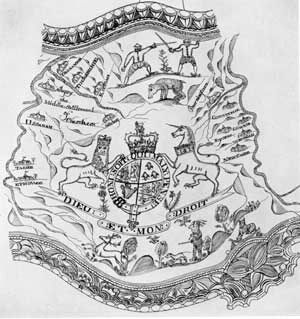

Another New York map horn (Illustration III), but of finer workmanship than that of Jotham Bemus, bears the inscription “Jacob Cuyler Fort Stanwix Septr 10, 1761.” This fort is a milestone in history for it was there, in 1777, that the American flag first flew in action. Jacob Cuyler was commissioned First Lieutenant in 1764 and served in the First Battalion of the Militia of the County of Albany, the Colonel of which was Sir William Johnson who in 1746 was invested by the Mohawks with the rank of a chief of that nation. The engraving represents the Hudson and Mohawk River valleys, Lake George, Lake Champlain, Lake Oneida and Lake Ontario, high spots of historic interest. At the base of the horn, labeled NEW YORK, are its harbor and shipping, churches and prominent buildings. One can see the old stone house in the fort down at the tip of the Battery where Jeffery Amherst, Conqueror of Canada and Commander-in-Chief in North America, was stationed for a time. On the opposite side ALBANY is pictured surrounded by a stockade, its church steeples topped by the conventional weathercock, and the river labeled “NORTH RIVER.”

Above this is a compact group of buildings labeled “LONDON.” Above the scene of London the MOHAWK RIVER enters the North River, the latter continuing up, flanked by the following forts: HALF MOON, STILLWATER, SARATOGA, FORT MILLER, ROYAL BLOOCK HOWS, and FORT EDWARD. These posts were not only strategical assets but also served as a protection to the English trade with the Indians, especially the fur trade between Oswego and Albany. The country, fifty miles beyond Albany, was virgin forest, penetrated only by trappers and Indians. The Mohawk River is flanked by the following: SCHNACETEDY, S. W. IOHN SONS, FORT HUNTER, STONRABBY, FORT HENRY, HARKMAN, and FORT STANWIX. A glance at a state road map explains the importance of this valley to the early colonies, and the significance of Mohawk friendship to the Dutch and English. This was the water-level route to the West– up the Hudson, along the Mohawk, and over the portage to Lakes Oneida and Ontario, and west through the Great Lakes to the Mississippi. In this connection are represented WOOD CREEK, ONYDA LAKE, FT. BROWNTON, TREE RIVER, SWEGO FALLS, FORT ONTARIO, NIAGARA, and LAKE ONTARIO. Showing the Lake George-Lake Champlain route from Albany to Canada are FORT GEORGE, TICONDROGA, CROWN POINT, SINT IOHN, MONT ROYAL and QUBECK.

Horns with maps of New England are much rarer than those of New York. One in the collection belonged to Jesse Starr (Illustration I), a Connecticut soldier who served in the fortifications about Boston during the Siege of 1775-6, and who while there decorated his horn with a map of Boston, in which the fortifications across the Neck are shown, and something of the surrounding country.

Jesse Starr was born in Norwich, Connecticut, where his parents, Vine and Mary (Street) Starr, lived for many years. He was twenty-one years old and living in Groton when he answered the first call for Connecticut troops, and enlisted May 8, 1775, in Capt. Spicer’s company in Colonel Parsons’ regiment. His company at once marched to Boston, and he there served in the camps at Roxbury. He was subsequently made a corporal and his military activities cover a period of five years during which time this powder horn was undoubtedly carried by him.

The extent of British activities in America is suggested by the St. Augustine horn (Illustration V) which represents the oldest town in the United States (founded by the Spaniards in 1565). It was used in the service of the army occupation in Florida (1762) and is engraved with the British arms, a general view of the town with its red roofs standing out conspicuously, the fort with the British flag flying triumphantly, and sailboats which give color and action to the picture. It is inscribed: “AN EXACT PROSPECT OF ST AUGUSTINE FROM THE LIGHT HOUSE THE METROPOLIS OF THE PROVINCE OF EASTFLORIDA” and “ENGRAV’D for MASTER CUMING.” The black roman lettering and touches of vermilion which heighten the engraving contrast effectively against the light tone of the horn. There is another horn in the Gilbert Collection delicately engraved with a map showing the harbors of “HAUANA” and “MATANSIA,” on the northwest coast of the island of Cuba, with the names and bird’s-eye views of the two towns and of the several forts protecting them. To have the St. Augustine and Havana horns in the same collection gives each of them an added historical interest, for Florida had been ceded by Spain to the British Crown in exchange for Havana.

Rare if not unique is the so-called Cherokee horn (Illustration II) engraved with a map of “The Middle Settlement of Cherokees” on the Tennessee (the present Little Tennessee) and the Tuckasegee rivers, territory which today is included in the County of Macon, North Carolina. The horn also bears the British arms. The Cherokees attached themselves to the English in the disputes which arose between the European colonizers, formally recognized the English king in 1730, and in 1755 ceded a part of their territory and permitted the creation of English forts, some of which are represented on this horn. Unfortunately, this amity was interrupted not long after: Lieutenant General Archibald Montgomerie, afterwards 11th Earl of Eglinton, raised a fine regiment of thirteen companies of Highlanders which became known as the 77th foot, and in 1757 took his regiment to America where it took part in much fighting against the Indians, especially the Cherokees whom he defeated in 1761. In this respect, it is interesting to note that until a few years ago among the contents of Eglinton Castle, Ayrshire in Scotland, were three powder horns engraved with plans of American historical interest. They were evidently engraved for the 11th Earl of Eglinton while serving with the British Army in America.

The study of these powder horns is a pleasant and easy way to learn much about early American history. Accordingly, I have set about making a record of historical examples, and officials of historical museums which preserve small collections have given me much valuable data. A pioneer in the appreciation of American powder horns was Rufus A. Grider (1817-1900), who lived in Canajoharie, New York, and taught art in the public schools there for about fifteen years. A selection of Professor Grider’s drawings were exhibited in February 1898, at the University of Pennsylvania in honor of President McKinley’s visit.