This post may contain Amazon Affiliate links for which I may receive compensation.

I recently read the book “Cinq siècles de pêche à la morue : Terre-Neuvas et Islandais (French Edition)” (Five centuries of cod fishing) written by Nelson Cazeils (in French, sorry!). The book discusses the history of cod fishing in all its aspects, but I was particularly fascinated by the discussion of when fishermen actually “discovered” North America, before the John Cabot, Jacques Cartier or Samuel de Champlain of this world!

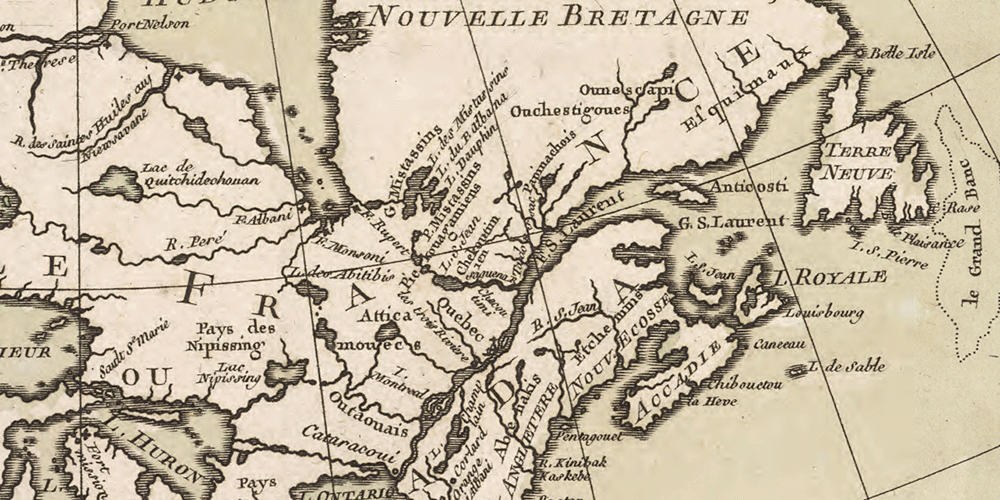

15th Century First Explorations of the Western Atlantic

The discovery of Newfoundland “banks” by the Basques, the Bretons, and the Normands can be traced back to the 15th century. At the time, the demand for fish (mandatory on Fridays and the 40 days of lent before Easter, as per Catholic rules) was increasing and fishing zones needed to be expanded.

The discovery of Newfoundland “banks” by the Basques, the Bretons, and the Normands can be traced back to the 15th century. At the time, the demand for fish (mandatory on Fridays and the 40 days of lent before Easter, as per Catholic rules) was increasing and fishing zones needed to be expanded.

Already in 1412, basque cod fishing boats were seen around Iceland. On Andrea Bianco’s 1436 atlas, we can read the word “stoc fis” (stick fish in German, ie. cod dried on sticks) in the Western part of the Atlantic.

It is believed that around 1470, European fishermen have reached Newfoundland banks. Then in 1497, John Cabot discusses how abundant fish banks were on the coasts of Eastern America. Cabot calls these lands “Baccallaos”, the name “locals” (native Americans or European fishermen?) give to fish, a word interestingly close to the word “bakailu”, the name given to cod by the Basques.

Until the beginning of the 17th century, “baccalao” indeed designates the Newfoundland banks or the lands close to them, such as Cape Breton.

16th Century – Fishing in Newfoundland’s Great Banks

At the beginning of the 16th century, Portuguese, Normands (Honfleur as early as 1506), Bretons (Bréhat 1508, Dahouet 1510), and Basques (Cap-Breton 1512) ports outfitted fishing boats for Newfoundland, Labrador, the coasts of the Gulf of the Saint-Laurent and Cape Breton Island.

Honfleur is one of the first ports to go fishing in Newfoundland waters (editorial note: it is not surprising then that major explorations such as Samuel de Champlain’s expeditions were leaving from Honfleur, because there was local knowledge of the waters and lands which were to be explored and settled.)

Between 1510 and 1540, about 50 French harbors are involved in this “rush” to newfound lands.

In 1534, Jacques Cartier writes that he saw a boat from La Rochelle (West French coastal port) on the south coast of Labrador, and in 1536 he writes that he came across “several boats from France as well as from Brittany” (Brittany was actually part of France in 1532) in the Bay of Saint-Pierre Island.

By 1559, La Rochelle outfits as many as 49 boats for Newfoundland in one year.

By 1578, Anthony Parkhurst, a British sailor estimates the number of European cod fishing boats in Newfoundland each year between 350 and 380, including 150 French boats.

17th Century North-American Settlements

But fishing did not necessarily mean permanent settlements. Some of the fishing boats were autonomous (preparing the fish onboard), and other fishing expeditions were settling temporarily (from May to the end of the summer) on the coasts of Newfoundland or of the Gulf of the Saint-Laurent.

Only later, around 1660, will permanent settlements be established in Plaisance, on the south-east coast of Newfoundland, and on Saint-Pierre et Miquelon. The Treaty of Utrecht (1713) even worsens the situation: in that Treaty, France lost Acadia (nowadays Nova-Scotia and New-Brunswick) and Newfoundland, retaining exclusive fishing rights on the east and west coast of Newfoundland but forbidden to have permanent settlements there. It forces France to exploit Ile Royale (Cap-Breton) and Ile St-Jean (Prince-Edouard Island) and to develop fishing in Labrador and Gaspesie.

It is only in the Treaty of Paris (1763) that France regains Saint-Pierre et Miquelon (small islands off the south-west coast of Newfoundland, still French today), where permanent habitants will settle. It is a dynamic fishing center, trading in particular with the Caribbean Islands.

Indeed, for five centuries, cod fishing has been an important economic activity for Brittany. In a future article, I will definitely come back and discuss the various marine maps made in the 15th century and identify the map which first mentioned the Great Banks of Newfoundland.

Another subject that also requires some discussion is the famous Charter of 1514, from the Abbaye de Beaufort, often misinterpreted as proof that Brittany fishermen had landed in North America (Newfoundland) before Christopher Columbus (1492).

Finally, the above book provides a few facts demonstrating that children as young as 8 were working on cod fishing boats. Such fact might bring some light to the endless discussion of the birth year of Samuel de Champlain, often argued on the basis of “how young he was when he first sailed overseas“.