This post may contain Amazon Affiliate links for which I may receive compensation.

I have to come to France to learn more about 15th-century expeditions to North America than I have while living in Canada or the US.

I knew that Bretons and Basques (respectively people from Brittany, France, and from the region between France and Spain) had been fishing and exploring the seawaters of Newfoundland and the Saint-Laurent before Samuel de Champlain and even before Jacques Cartier.

Unfortunately, I had never found much more information about it… until this book (in French) that I just read: “Aventuriers bretons sur les océans (La bibliothèque océane) (French Edition)” (Bretons’ adventurers across the oceans), written by Georges G. -Toudouze. Fascinating indeed, even though I found the writing style made it a tough read.

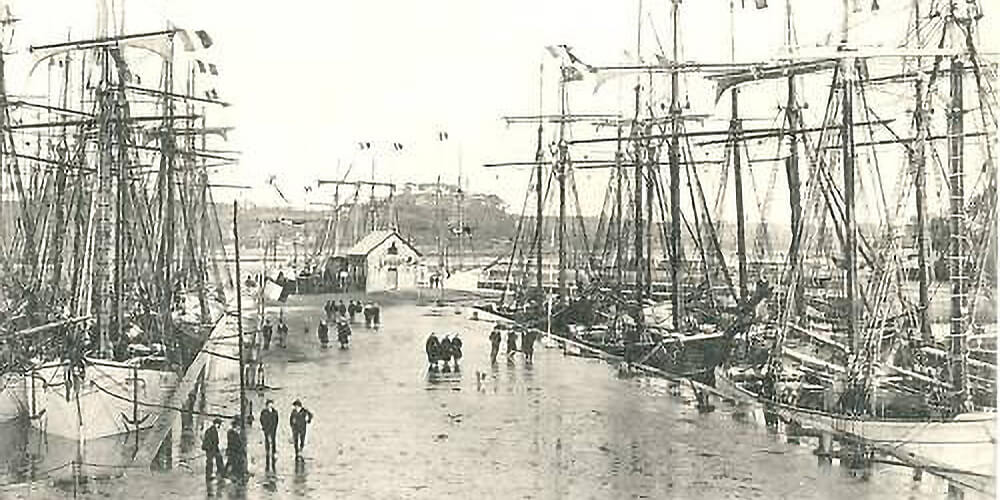

Brittany fishermen had been fishing cod in Newfoundland waters since the middle of the 15th century, so much so that this region of Eastern Canada or Newfoundland itself (sources need to be checked as the name “terre neuve” was used for a broader region than Newfoundland, including Labrador and Cape Breton) was usually called “la Terre-aux-Bretons” (Bretons’ soil).

There is actually a manuscript dated and signed December 14, 1514, written by the monks of the Abbaye de Beauport (near Paimpol, Brittany) which discussed the fact that fishermen from the close-by island of Bréhat were fishing in Newfoundland waters on a regular basis, for as long as sixty years, which means they started fishing there sometime between the year 1454 and the year 1514.

More precisely the manuscript record states that the monks collected a tax on cod, whitings and other fishes fished on the coast of Brittany, as well as Newfoundland, Iceland, and other places, that the people of the Island of Bréhat admit they have been paying, for two, three, four, five, ten, twenty, thirty, fourty, fifty, sixty years (“peschés tant en la coste de Bretagne, la Terre-Neuve, l’Islande que ailleurs, une dîme que les gens de l’isle de Bréhat reconnaissent payer depuis deux, troys, quatre, cincq, dix, vingt, trente, quarante, cinquante, sexante ans”).

And in 1526, a captain from Saint-Malo, Nicolas Le Don, decided to explore “further West” and discovered an unknown coast, where he saw “unfriendly savages”, with whom he exchanged some golden necklaces and jewelry.

In comparison, it is only in 1534 that Jacques Cartier reaches the now-Canada coast during his first expedition. The book goes on to explain in great detail how yearly fishing campaigns were organized in the subsequent years… 1553, 1554, etc., years during which they were constantly fighting the Basques.

During this second half of the 16th century, the Newfoundland waters were so much recognized “bretonnes’’ that in 1591 – says a British historian – British fishermen asked the “Malouins” (the name given to people of Saint-Malo) the authorization to go and fish around Newfoundland, Brittany waters!

These are simply fishing expeditions rather than settlements you might say. After all, the date of the first settlement in Canada is 1603 when Samuel de Champlain participated in his first expedition, you are thinking.

Well, the book again brings us some more surprises, and discussed an expedition in 1597-1598 led by Troïlus, Marquis Du Mesgouez de La Roche Helgomarc’h, an adventurer from Saint-Malo, during which 50 “settlers” from the prisons of Rouen, were left on the “Ile de Sable”. When he sent a captain, named Chefdhostel in 1603 to go and see how the settlers were doing, the latter only found 11 alive, or rather half-dead of starvation.

The author doesn’t say where this island is located, but Wikipedia came to my rescue (see Ile de Sable (Sable Island) and even mentions this “brief attempt of colonization”! Additionally, look at some old maps of the time, and you’ll often see this island somewhere between Newfoundland and the Canadian continent.

Fascinating tales and a fascinating book indeed!