“Defining Lines: Cartography in the Age of Empire” was a student-curated exhibit at the Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University, NC, from September 19 to December 15, 2013. It displayed maps from the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, from the 16th to 20th centuries.

As I write this article, unfortunately, the exhibit has ended, but you can still enjoy its rich content, thanks to the video presentation “Defining Lines: Student Curators Gallery Talk, October 3, 2013” (see below) and the website of the exhibit, where each map is presented in details, with the support of texts and videos.

The exhibit reminds us that, at the time of the colonial empires, maps were not only tools for the explorers and voyagers to go from place to place, but had a crucial political role. Since the 16th century, Europe conquered the world, and cartography was used to define and claim the territories under the control of every power. From atlases and wall maps to manuscripts, maps were not the work of one cartographer, but they were visual texts, collecting information from previous maps and from books written by explorers (see Carta Marina article).

Maps were decorative, educational, but also political statements. As stated in the text presenting the exhibition: “These maps delineated colonial holdings, visualized space, and reinforced control over people, places, and things alike.” They are still today a “popular medium through which we understand the world and the man-made lines that define and ultimately control it.”

Short Descriptions of the Maps Exhibited:

Africa

As mentioned on the exhibition website, from the 15th to the 20th century, trade was the main reason for the colonization of Africa by a number of European powers. The Portuguese explorers were the first to round the Cape of Good Hope at the turn of the 15th century and to establish trading posts on the West Coast of Africa in the mid-1400s.

Then a number of nations, including Britain, Denmark, and the Netherlands had trading posts on the African coastline, but except in South Africa, the exploration and settlements were limited to the coast, as Africa’s natural terrains (such as the Sahara Desert and Central Africa’s tropical forests) were great barriers for expansion.

Even in the 19th century, the penetration of the African continent started with the exploration of the four main rivers (Nile, Niger, Congo, and Zambezi).

- “A New Map of Africa, from the best Authorities” by John Lodge

Printed in the 1780s by John Lodge, an engraver with knowledge in producing inexpensive prints, the map is a copy of a previous map of Africa, by cartographer Thomas Kitchin. Its low cost allowed the British general public to familiarize itself with Africa. - “General Chart of the Colony of the Cape of Good Hope” by John Barrow

Released in 1801 and extensively circulated, Barrow’s map is considered the first comprehensive map of South Africa’s British colony. The Dutch who rule the Cape Colony until the British seized it in 1795 had produced maps, but they were unknown to the British. John Barrow was the private secretary of Lord Macartney, the governor of the Cape. He published the map as part of his travel narrative “An Account of Travels into the Interior of Southern Africa, in the years 1797 and 1798.“ - “Map of the west coast of Africa from Sierra Leone to Cape Palmas” by Anthony Finley

This map of the colony of Liberia was first published in 1830 in the 13th Annual Report of the American Society for Colonizing the Free People of Color of the United States and in the annual atlas of its author, Anthony Finley. It shows in detail the organization of the colony. - “Africa” by John Bartholomew, Jr.

Published in the 1879 edition of Black’s General Atlas of the World by the Scottish mapmaking firm John Bartholomew & Son, just before European powers divided up African unclaimed lands among themselves, the map shows vast blank spaces in regions still unknown. It also shows the Mountains of Kong, fictitious mountains in West Africa which were included on many 19th century maps. It also displays the travel routes of well-known European explorers of the time. - “Spezial-Karte von Afrika” by Hermann Habenicht

Published in the 1880s by Justus Perthes publishing house, the map speaks of Germany’s rise as a colonial power. For its creation, the cartographer Hermann Habenicht used a vast number of sources including official surveys, geographical journals, and the itineraries of famous explorers such as Englishman David Livingstone and the American Henry Morton Stanley. - “Deutsch-Ostafrika” by Max Moisel

This map of German East Africa was published in 1910. It is the creation of Max Moisel, a cartographer specialist of Africa, who worked for the Berlin publishing company Dietrich Reimer. It describes the colony in great detail, including the location of the natural resources in the region.

India

The first trading post in India dated from 1611 and was set up by the British East India Company. Until 1740, both French and British trading posts were limited. After 1760, however, the British East India Company expanded its activities there, tried to raise taxes and establish land ownership.

The exhibition website doesn’t provide further details about the colonization of India, but as we well know, it was under British rule until 1947.

- “The Country round Trichinopoly with the Camps and Marches of the English and French Troops in 1753 and 1754″ by Thomas Jefferys

This 1760 map of French and British encampments is the work of cartographer, engraver, and commercial printer Thomas Jefferys, the official cartographer of British King George III. Thomas Jefferys is also known for his maps of British territories in North America, during the Seven Years’ War. - “Ad Antiquam Indiae Geographiam Tabula” by Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville

Cartographer Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville, the geography tutor of King Louis XV, was well known and often copied throughout Europe for the quality of his maps. Even Thomas Jefferson used his maps in planning the Lewis and Clark expedition. As his map-making business became more stable, he could pursue his personal interest in antiquity. This undated map of India is an example of d’Anville’s ancient maps. - “Carte Générale du Cours du Gange et du Gagra” by Joseph Tiefentaller

Joseph Tiefentaller (1710-1785) has traveled for several years in India, researching the local customs, religions, languages, and flora and fauna. His language skills allowed him to obtain geographical information from locals. His friend Abraham-Hyacinthe Anquetil Du Perron, to whom he had sent sketches and notes, presented some of his works to the French Academy of Sciences. This map, in French and Persian, is one of these maps. - “Neueste Karte von Hindostan” by Franz Anton Schrämbl

Published in 1800, this map was part of the Algemeiner Grosser Atlas, one of the first Austrian world atlases. For this atlas, Schrämbl chose works from renowned cartographers, such as Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville, James Rennell, and Thomas Kitchin. This map of India, a reproduction of James Rennell’s 1782 map of Hindoostan (modern-day Indian peninsula), shows an unprecedented amount of details of the region. Indeed, Rennell had been the first to use physical surveys rather than travel journals. The cartouche was also reproduced from the original map and is an emblem of Britain’s imperialism (interesting fact in an Austrian atlas). - “Stanford’s Map of India” by Edward Stanford

Edward Stanford (1826-1904) had a publishing business (which still exists today) and had taken an interest in cartography related to Britain’s imperialism. When war broke out in India in 1857, he published this map within one year, probably to try to profit from an increased popular interest in affairs in India. Note that the map includes a table listing all various Indian regions with the dates the British acquired them. - “The Residency, Palaces, & c. of Lucknow” by Edward Weller

Edward Weller’s map was published as part of a series of maps from around the world in the British Weekly Dispatch newspaper. It describes the 1857 Sepoy Rebellion which took place in Northern India, and during which Lucknow was the site of a prolonged siege. The sepoys had rebelled when they learned that the grease on the cartridges of the Enfield rifle their regiments were using, was in fact composed of cow and pig fat, the consumption of which was forbidden by both Hindus and Muslims. The sepoys had seen that as a disregard to their culture and religion.

Latin America

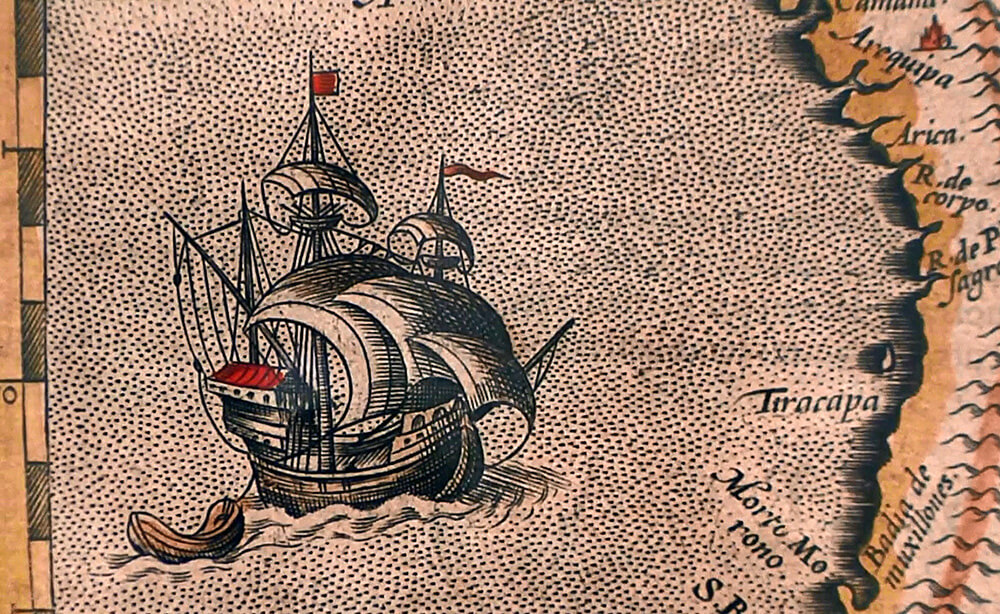

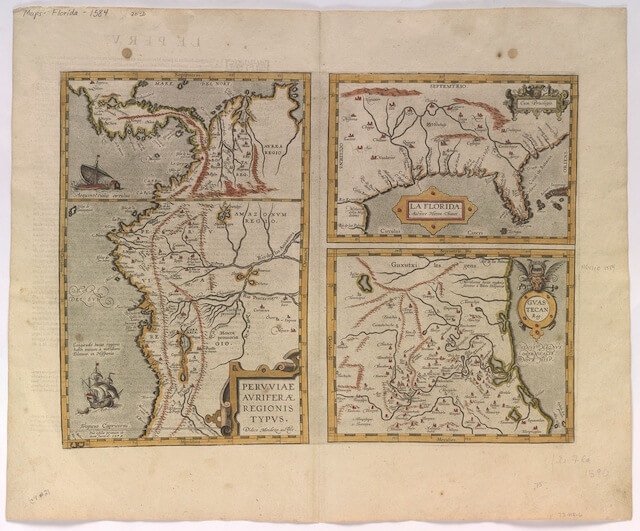

- “Maps of Peru, Florida, and Guastecan (Huasteca) from Theatrum Orbis Terrarum” by Abraham Ortelius

Florida Peru and Guastecan map – Abraham Ortelius (1584) Courtesy of the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Duke University

Abraham Ortelius is considered the publisher of the first modern atlas.

In its 3rd edition, Theatrum Orbis Terrarum, there are 3 maps of the New World and 105 maps of the rest of the world. The map Peruviae Auriferae Regionis Typus is one of the first widely published maps of Peru, Florida, and Guastecan (Guastecan shows a portion of east-central Mexico along the Gulf of Mexico coastline).

For his atlas, Ortelius borrowed the engravings of maps created by others and added entertaining descriptions of how people lived in these regions. The map of Peru is attributed to Didaco Mendezio, while the Florida map is attributed to Jeronimo de Chaves (copied from an earlier manuscript by Alonso de Santa Cruz).

The creator of the Guastecan map is unknown. Explorers’ letters and travelogues from Ponce de Leon, Cabeza de Vaca, and Vazquez de Allyon helped Ortelius complete the texts.

- “Typus Geographicus: Chili a Paraguay Freti Magellanici, &c.” by Guillaume de l’Isle

This map of Chile, Paraguay, and the Magellan Strait was published in 1703 and republished by the Homann Heirs firm as Typhus Geographicus Chili Paraguay, etc in 1733. Its cartographer Guillaume de l’Isle is considered as one of the major contributors to the science of cartography (along with Ptolemy and Mercator). The work of the Chilean Jesuit Ovalle (book and map of Chile) was a vital source for de l’Isle in the production of this map. - “Carte du Mexique et de la Nouvelle Espagne” by Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville

Jean-Baptiste Bourguignon d’Anville (1697-1782), a Paris native, produced 200 maps during his lifetime. This map was published by Remondini, a publishing firm established in 1647 and considered one of the greatest ones in Europe by 1773. - “Plano del Pueblo y Rio de Suipacha situado en la Probincia de Chichas” by Manuel Pantosa y Moreno

A Spanish cartographer created this “Plan of the city and river of Suipacha situated in the province of Chichas,” a small town in Bolivia, then known as Alto Peru. Following the Battle of Suipacha (1810), the Spanish surveyed the natural defenses of the region, which they did not want to lose. In 1814 this map was the result of such a survey. Blocks of text describe the various locations and the manner the river could be used as a defense against any invading forces. - “Map from Alto Perù Cartas Topograficas” by Manuel Pantosa y Moreno

Unlike other maps in the exhibit, which were printed from engravings, this map is hand-drawn, and little is known about its mapmaker Manuel Pantosa y Moreno. The map – showing part of now Bolivia – is divided into 8 partitions, four of them belonging to one Catholic Mission and the 4 other four belonging to individual Missions. At the top, the regions were labeled “terrenos incognitos” (unknown territories) which leaves a lot to the imagination! - “A Map of South America: According to the Latest and Best Authorities” by Anthony Finley

In the early nineteenth century, the US was showing an interest in expansion to the West and to the South. Part of Henry S. Tanner’s atlas, this map of South America was produced by Anthony Finley, about whom little is known, except for the fact he was working in Philadelphia publishing circles. At the time of publication, a majority of former Latin American colonies had recently regained independence, following the Spanish-American war.